Less than one hundred years after declaring independence from the British and becoming a nation, the United States of America was ripped to shreds by its bloodiest conflict ever: The American Civil War.

Some 620,000 men lost their lives fighting for both sides, although there’s a reason to believe this number may have been closer to 750,000. Which means, the total comes out to around 504 people per day.

Think about that; let it sink in — that’s small towns and entire neighborhoods being wiped out each and every day for nearly five years.

To drive this home even further, consider that roughly the same amount of people died in the American Civil War as all other American wars combined (450 000 in WWII, 120 000 in WWI, and roughly another 100 000 from all the others fought in American history, including the Vietnam War).

By why did this happen? How did the nation succumb to such violence?

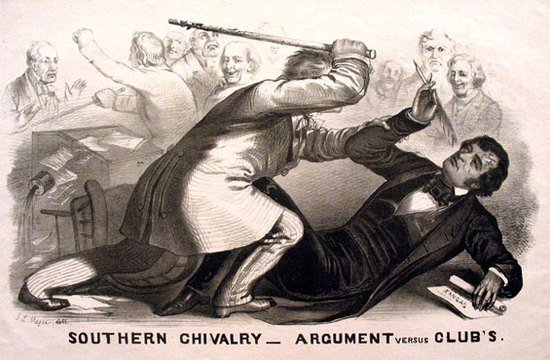

The answers are in part political. Congress during this time period was a heated place. But things went deeper. In many ways, the Civil War was a battle for identity. Was the United States a unified, inseparable entity as Abraham Lincoln claimed? Or was it merely a voluntary, and potentially temporary, collaboration of independent states?

But how did this happen? After everything the United States of America was founded on less than a century before — freedom, peace, reason — how did its people find themselves so divided and resorting to violence?

Did it have something to do with the whole “ ‘all men are created equal’ but, oh yeah, slavery is cool” issue? Perhaps.

Without a doubt, the slavery question was at the heart of the American Civil War, but this massive conflict wasn’t some moral crusade to end bonded labor in the United States. Instead, slavery was the backdrop for a political battle taking place along sectional lines that grew so fierce it eventually led to the Civil War. There were numerous causes that led to the Civil War, many of which developing around the fact that the North was becoming more industrialized while the Southern states remained largely agrarian.

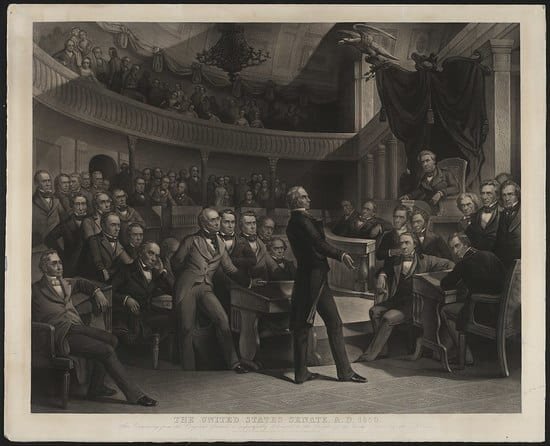

For most of the Antebellum Period (1812–1860), the battleground was Congress, where differing opinions about whether or not slavery was to be allowed in newly acquired territories drove a wedge along the Mason-Dixon Line that separated the United States into Northern states and Southern states.

Because of this, Congress during this time was a heated place.

But as real fighting began in 1861, it was clear things went deeper; in many ways, the Civil War was a battle for identity. Was the United States a unified, inseparable entity, destined to last the entirety of time, as Abraham Lincoln claimed? Or was it merely a voluntary, and potentially temporary, collaboration of independent states?

The origins of the Civil War remain a matter of great debate, with a strand of Southern collective memory emphasising the belligerence of the North and states rights, rather than the issue of slavery.

Table of Contents

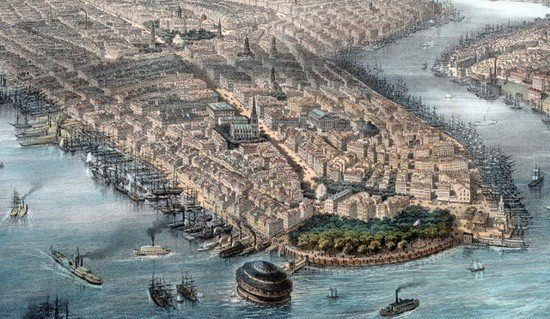

The North on April 13, 1861…

You awake on the morning of April 13, 1861 in Lowell, Massachusetts. Your footsteps as you walk down the street are echoed by the clatter of horseshoes and wagon wheels. Vendors yell from street stalls, informing the crowd walking by of the day’s specials on potatoes, eggs, chicken, and beef. It will be some months before the market displays more color.

As you approach the factory, you come across a group of Negroes milling about near the entrance, standing around and waiting to see if there’ll be a shift for them.

Why they can’t just get a stable job like the rest of us I don’t know, you think. It must be that Negro way of being that makes them not fit for work. It’s a shame, really. We’re all God’s children, just like the pastor says. But there’s not much you can do to save them, so it’s usually best to just avoid them.

You’re not saying they should be thrown into bondage. God certainly wouldn’t want that. And slavery makes it harder for everyone, what with the plantation owners grabbing all the land and keeping it from everyone else. But what else can you do? Send ‘em back to Africa, maybe — can’t expect them to adapt to life here, so let ‘em go home. They’ve got Liberia just sitting there if they want to go. You can’t imagine it’s much worse than what they’re doing here, just lazing around, hoping to find work, getting people all worked up.

You try to push these thoughts from your mind, but it’s too late. Seeing those Negroes in front of the factory has got you to thinking again, about what’s going on in the great world outside Lowell. The nation is on the brink of Civil War. The Southern Confederate states of America had announced their secession, and Abraham Lincoln is showing no signs of backing down.

But good on him, you think. That’s why I voted for the man. Lowell is the future of the United States of America — factories, people working and making much better money than they ever made out in the fields. Railroads connecting cities, and bringing goods that people need at a price they can afford, providing work for thousands more men along the way. And protective tariffs, to keep British goods away and to give the people and this nation the chance to grow.

That’s what those stubborn Southern Confederate states don’t see. The country can’t just keep planting cotton and shipping it overseas with no tariffs. What happens when the land goes bad? Or people start to prefer wool? America has got to move forward! If slavery is allowed in the new territories, it will just be more of the same.

As you continue to the factory, you see the man who sells the newspaper standing in the front entrance, as he does everyday. You reach into your pocket for the penny to pay him, grab the paper, and head in for a day’s work.

Hours later, when you walk out just as the cool evening breeze sweeps around you, the newspaper man is still there. This is surprising, as he normally goes home after selling out his papers in the morning. But you see in his arms a fresh stack.

“What’s this?” you ask as you approach him.

“Boston Evening Transcript. Special edition. Courier brought it in just a few hours ago,” he says as he holds one out to you. “Here.”

You grab for it, and, catching a glimpse of the headline, you fumble, failing to find the coin to pay him. It reads:

WAR BEGUN

The South Strikes First Blow

The Southern Confederacy Authorizes Hostilities

The man is speaking, but you can’t hear the words over the blood thumping in your ears. ‘WAR BEGUN’ rings in your head. You reach numbly into your pocket for the penny you owe and grasp it with sweaty fingers, handing it to the man as you turn and walk away.

You swallow dryly. The idea of war is a scary one, but you know what you must do. Just like your father and your father’s father: defend the nation so many have worked so hard to build. Never mind the Negro, this is about America.

You don’t want to go to war, but you must take a stand for this country, so noble and so divine, and keep it together forever, as God intended.

This is happening because we disagree on slavery, you think to yourself, clenching your jaw, but I’m going because I will not let this nation fall apart.

You’re an American first and a Northerner second.

Within a week you will be marching towards New York, and then on to the nation’s capital, joining up with the army and having upended your life in defense of the eternal, right, United States of America.

The South on April 13, 1861…

READ MORE: Who Invented the Cotton Gin? Eli Whitney and Cotton Gin Impact on America

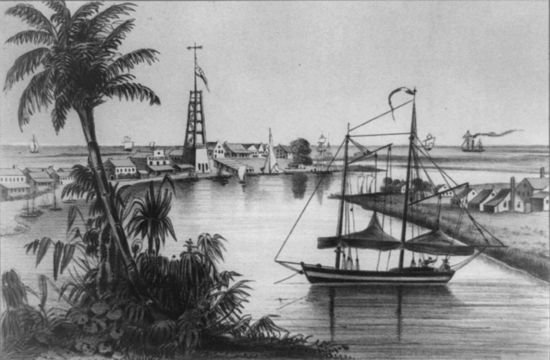

As the sun starts peaking over the Georgia pines in the quiet lands surrounding Jesup, your day is already hours gone. You’ve been up since the predawn light, running the till over the bare soil where you will soon plant corn, beans, and squash, hoping to sell it all — along with the peaches that fall from your trees — at the Jesup market all summer. It doesn’t make you much, but it’s enough to live by.

Usually, at this time of year, you’re working on your own. There’s not much to do just yet, and you’d rather the kids stay inside and help their mother. But this time, you’ve got them out with you, and you’re walking them through the steps they’ll need to follow to keep the farm running in the months you’re gone.

By just afternoon, you’ve finished what needs doing at the farm for the day, and you decide to ride into town to get the seeds you need and to settle an account with the bank. You want to have everything squared away.

You don’t know when you’re leaving, but Georgia has declared itself independent of Washington, and if it came time to defend that with force, you were ready.

There were more than a few reasons why, the most important being the North’s repeated aggression against the Southern states way of life.

They want to tax us all and then use the money to build what will only benefit the North, leaving us behind, you think.

So what about slavery? That’s a states’ issue… something that should be decided by those on the ground. Not by some fancy politicians in Washington.

Not for nothing, but how many Negroes do these Republicans from New York see on a daily basis? You see ‘em every day — hanging around Jesup with those big eyes. You don’t know what they’re up to, but looking the way they do, it can’t be nothing good.

All’s that you can say is that you don’t have no slaves, but you can be sure the Negroes under the control of Mr. Montogmery, who has his plantation just up the road, don’t cause no trouble for White folks, not like the ‘free’ ones living in town.

Down here in Georgia, slavery just works. Simple as that. In the territories out west trying to become states, that should have been their decision, too. But them Northerners, butting their heads into everything, wanted to go and make it illegal.

Now, you think to yourself, why would they want to take a states’ issue and make it a national one, if they didn’t have eyes on changing the way we do things around here? That’s just unacceptable. There ain’t no other choice but to fight.

This line of thinking always gets you worked up because, of course, the idea of Civil War doesn’t sit too well with you. It’s war, after all. You’ve heard your daddy’s stories, and the ones his daddy told, too. You ain’t stupid.

But there comes a time in a man’s life when he must make a choice, and you just can’t imagine a world where Yankees sit in a room by themselves, talkin’ and deciding what goes on in Georgia. In the South. In your life. You will not stand for it.

You’re a Southerner first and an American second.

So, when you reach town and find out fighting has begun in Fort Sumter, Charleston, South Carolina, you know the moment has arrived. You will return home to continue teaching your son, while preparing yourself for the Civil War. Within just a few weeks, you’ll be marching with the Army of Northern Virginia to defend the South and its right to determine its own destiny.

How the American Civil War Happened

The American Civil War happened because of slavery. Period.

People may try to convince you otherwise, but the reality is they don’t know the history.

So here it is:

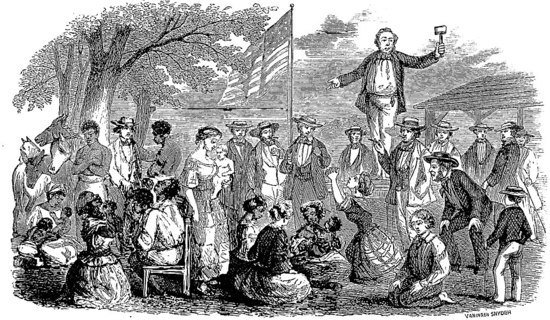

In the South, the main economic activity was cash-crop, plantation agriculture (cotton, mainly, but also tobacco, sugarcane, and a few others), which relied on slave labor.

This had been the case since the colonies first came into existence, and although the slave trade was abolished in 1807, the Southern states continued to rely on slave labor for their money.

There was little in the form of industry in the South, and in general, if you weren’t a plantation owner, you were either a slave or poor. This established a rather unequal power structure in the South, where rich White men controlled almost everything.

Surprise!

What’s more, these rich powerful White men believed their businesses could only be profitable if they used slaves. And they managed to convince the public at large that their lives depended on the continuaton of the institution of slavery.

In the North, there was more industry and a larger working class, which meant wealth and power was more equally distributed. Powerful, rich, landowning White men were still mostly in charge, but the influence of lower social classes was stronger which had a dramatic effect on politics, specifically on the issue of slavery.

Over the course of the 1800s, a movement to end the institution of slavery — or to at least stop its expansion into new territories — grew in the North. But this was not due to a majority of Northerners feeling that owning other people as property was a horrifying practice that defied all morality and respect for fundamental human rights.

There were some who felt this way, but the majority hated it because the presence of slaves in the workforce drove down wages for working White people, and slave-owning plantations absorbed new lands that free White men could otherwise buy. And God forbid the White man should suffer.

As a result, the American Civil War was fought over slavery, but it didn’t touch the foundation of White supremacy upon which America was founded. (This is something we should never forget — most especially today, as we continue to work through some of these very same fundamental issues.)

Northerners also sought to contain slavery because of the three-fifths stipulation in the US Constitution, which said that slaves counted as three-fifths of the population used to determine representation in Congress.

READ MORE: Three-Fifths Compromise

The spread of slavery to new states would give these territories more people to count and therefore more representatives, something that would give the pro-slavery caucus in Congress even more control over the federal government and could be used to protect the institution.

So, from everthing covered so far, it’s clear the North and the South didn’t see eye to eye on the whole slavery thing. But why did this lead to the Civil war?

You would think the White aristocrats of 19th century America could sort out their differences over martinis and oysters, eliminating the need for guns, armies, and lots of dead people. But it’s actually a bit more complicated than that.

The Expansion of Slavery

While the American Civil War was caused by a fight over slavery, the main issue regarding it leading up to the Civil War was not actually about abolition. Instead, it was about whether or not the institution should be expanded into new states.

And in lieu of moral arguments about the horrors of slavery, most of the debates about it were really questions regarding the power and nature of the federal government.

This is due to the fact that, during this period, the United States was encountering issues not thought of by those who wrote the Constitution, leaving the people of the day to interpret it as best they could to their present situation. And since its establishment as the guiding document of the United States, one major debate about Constitutional interpretation was about the balance of power between states and the federal government.

In other words, was the United States a cooperating “union” with a central government that held it together and enforced its laws? Or was it merely an association between independent states, bound by a contract that had limited authority and that could not interfere with the issues occuring at the state level?The nation would be forced to answer this question during a time known as the American Antebellum Period due to its westward expansion, driven in part by the “Manifest Destiny” ideology; something that claimed it was God’s will for the United States to be a “continental” nation, stretching from “sea to shining sea.”

Expanding West and the Slavery Question

The new territory gained in the West, first from the Louisiana Purchase and later from the Mexican-American War, opened the door for adventurous Americans to move and pursue what we can probably call the roots of the American dream: land to call your own, successful business, the freedom to follow your interests both personal and professional.

But it also opened up new lands plantation owners could buy up and man with slave labor, closing this unclaimed land in open territories to free White men, and also limiting their opportunities for gainful employment. Because of this, a movement began to grow in the North to stop the expansion of slavery into these newly opened areas.

Whether or not slavery was allowed depended significantly on where the territory was located, and by extension, the type of people who settled it: slavery-sympathetic Southerners, or Northern Whites.

It’s important to remember, though, that this anti-slavery stance in no way represented progressive racial attitudes in the North. Most Northerners, and even Southerners, knew that containing slavery would eventually kill it — the slave trade was gone, and the country as a whole was less dependent on the institution.

Containing it to the South and banning it in new territories would eventually make slavery irrelevant, and it would construct a Congress with the power to ban it forever.

But this didn’t mean people were ready to live alongside those formerly in bondage. Even Northerners were extremely uncomfortable with the idea of all the nation’s Negro slaves suddenly becoming free, and so plans were developed to solve this “problem.”

The most drastic of these was the establishment of the colony of Liberia on the West African coast, where freed Black people could settle.

America’s charming way of saying, “You can be free! But please go do it somewhere else.”

Controlling the Senate: North v. South

Nevertheless, despite the rampant racism throughout 19th century United States of America, there was a growing movement to prevent slavery from expanding. The only way to do this was through Congress, which was frequently split in the 1800s between slave states and free states.

This was significant because as the country grew, new states needed to announce their position towards slavery, and this would affect the balance of power in Congress — specifically in the Senate, where each state got, and still gets, two votes.

Because of this, both the North and the South tried their best to influence each new state’s position on slavery, and if they could not, they would attempt to block that state’s admission to the Union so as to try and maintain the balance of power. These attempts created political crisis after political crisis throughout the 19th century, with each one showing more than the last just how divided the nation was.

Repeated compromises would delay the Civil War for decades, but eventually it could no longer be avoided.

Compromise After Compromise After Compromise

While this story eventually ends in the American Civil War, no one, up until about 1854, was really trying to start a war. Sure, several senators wanted to have a go at one another — something that actually did happen in 1856, when a Southern Democrat, Preston Brooks, nearly beat Senator Charles Sumner to death with his cane in the Capitol building — but the aim was to at least try and keep things civil.

This is because, throughout the 1800s during the Antebellum era, most politicians saw the issue of slavery as a small one that could be easily solved. Of the many layers of this issue, the biggest concern was the effect it would have on the nation’s mostly White citizens, and not its slaves, the majority of whom were Black.

In other words, it was an issue affecting White men that needed to be solved by White men, even when there were hundreds of thousands of Black slaves living in the United States of America at the time.

It wasn’t until the 1850s that the issue became more ingrained in the public debates occurring around the United States, eventually leading to violence and the Civil War.

When the issue did come up, though, it stalled American politics. The crisis was averted by compromises meant to “solve” the slavery issue, but, in the end, they didn’t. Instead, they led the way to the outbreak of a conflict that would cost more Americans their lives than any other war to date.

Organizing New Territory

The conflict 19th-century politicians were trying to solve actually had its roots in the signing of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. This was one of the few pieces of legislation made by the Confederation Congress (the one in power before the signing of the Constitution) that actually had an impact, although they probably had no idea the chain of events this law would set in motion.

It established rules for the administration of the Northwest Territory, which was the area of land west of the Appalachian Mountains and north of the Ohio River. In addition, the Ordinance laid out how new territories could become states (population requirements, constitutional guidelines, the process for applying and being admitted to the Union), and, interestingly enough, it banned the institution of slavery from these lands. However, it did include a clause that said fugitive slaves found in the Northwest Territory had to be returned to their owners. Almost a good law.

This gave the Northerners and anti-slavery proponents hope, because it set aside a huge territory of “free states.”

When America was born, there were just thirteen states. Seven of them did not have slavery, whereas six states did. And when Vermont joined the Union in 1791 as a “free” state, it became 8–6 in favor of the North.

And with this new law, the Northwest Territory was a way for the North to continue expanding its lead.

But over the first 30 years of the Republic, as the Northwest Territory turned into Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), and Illinois (1818), the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama all joined the Union as “slave” states, leveling things up to 11 all.

We shouldn’t think of the adding of new states as some sort of chess game being played by American lawmakers — the process of expansion was far more random, as it was influenced by so many economic and social motivations — but as slavery became an issue, politicians realized the importance these new states would have in determing the fate of the institution. And they were ready to fight about it.

Compromise #1: The Missouri Compromise

The first round of the fight came in 1819, when Missouri applied to be a state that allowed slavery. Under the leadership of James Tallmadge Jr., Congress reviewed the state’s constitution — since it had to be approved for the state to be admitted — but some Northern senators began advocating for requiring an amendment that would ban slavery to Missouri’s proposed constitution.

This obviously caused Southern states congressmen to oppose the bill, and a big argument broke out between the North and the South. No one threatened to leave the Union, but let’s just say things got heated.

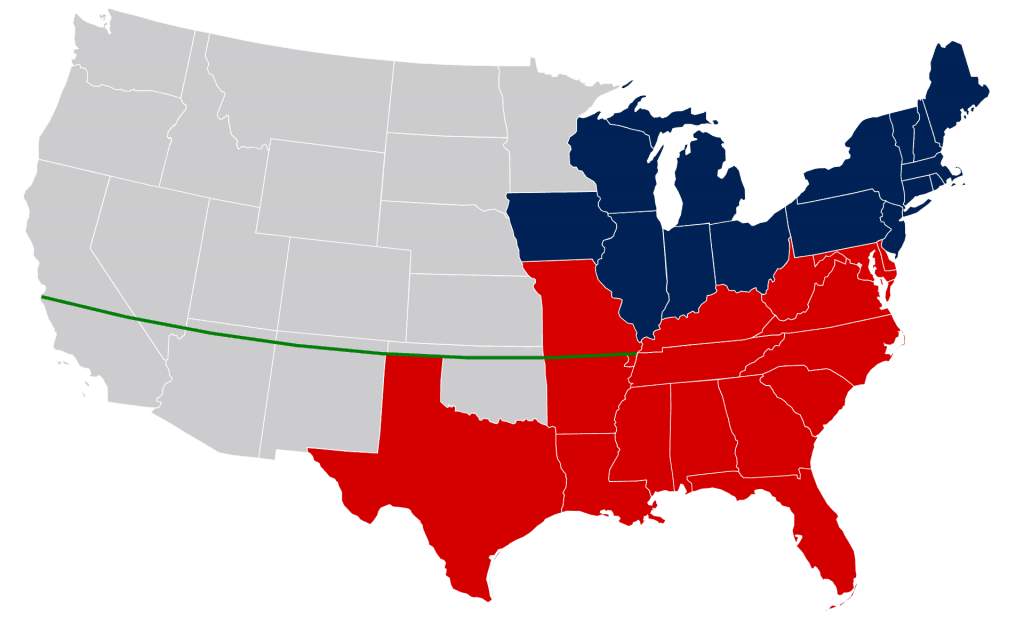

In the end, Henry Clay, famous for brokering The Great Compromise during the Constitutional Convention, negotiated an agreement. Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, but Maine would be added to the Union as a free state, keeping things level at 12–12.

Furthermore, the 36º 30’ parallel was established as a boundary — any new territories admitted to the Union north of this line of longitude would not have slavery, and any south of it would be open to slavery.

This solved the crisis for the time being, but it did not remove the tension between both sides. Instead, it just kicked it further down the road. As more and more states were added to the Union, the issue would appear continuously.

For some, the Missouri Compromise actually made things worse, as it added a legal element to sectionalism. The North and the South had always been different in their political views, economies, societies, culture, and a lot more, but by drawing an official boundary, it quite literally split the nation in two. And over the next 40 years, that split would grow wider and wider until it was cavernous.

Compromise #2: The Compromise of 1850

All things considered, things went smoothly for the next twenty or so years. However, by 1846, the issue of slavery had started to come up again. The United States was at war (surprise!) with Mexico, and it appeared they were going to win. This meant even more territory added to the country, and politicians had their eyes on California, New Mexico, and Colorado, in particular.

The Texas Question

Elsewhere, Texas, after breaking free from Mexican control and existing as an independent nation for ten years (or until present day if you ask a Texan), joined the Union in 1845 as a slave state.

Texas started stirring things up, as it tends to do, when it made absurd claims to territory in New Mexico that it had never really controlled. Apparently just figuring, what the hell!

Representatives from Southern Confederate states supported this move with the reasoning that the more territory where slavery was allowed the better. But the North opposed the claim for the exact opposite reason — from their perspective, more territories with slavery was definitely not better.

Things got worse in 1846 with the Wilmot Proviso, which was an attempt by David Wilmot from Pennsylvania to ban slavery in the territories acquired from the Mexican War.

This greatly irritated Southerners because it would have effectively nullified the Missouri Compromise — much of the land to be acquired from Mexico was south of the 36º 30’ line.

The Wilmot Proviso did not get passed, but it reminded Southern politicians that people from the North were beginning to look more seriously at wiping out slavery.

And, more importantly, the Wilmot Proviso initiated a crisis in the Democratic party and drove a wedge between Democrats, eventually causing the formation of new parties that all but eliminated Democratic influence in the North and eventually the government in Washington.

It wasn’t until well after the American Civil War that the Democratic Party would once again return to prominence in the federal political system, and it would do so as an almost entirely new entity.

It’s also thanks to the split of the Democratic Party that the rise of the Republican Party could take place, a group that’s been present in American politics from its founding in 1856 to this very day.

The South, which was primarily Democrat (an entirely different Democrat than is around today), correctly saw the fracture of the Democratic party and the rise of powerful new parties based entirely in the North as a threat. In response, they began to ramp up their defense of slavery and their right to allow it in their territory.

The California Question

The issue of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico came to a head when California was included in the treaty terms with Mexico and applied to become a state in 1849, just one year after it was made part of the US. (People flocked to California in 1848 thanks to the irresistible allure of gold, and this quickly gave it the population necessary to apply for statehood.)

Under normal circumstances, this might not be a big deal, but the thing with California is that it is both above and below that imaginary slavery border; the 36º 30’ line from the Missouri Compromise runs straight through it.

Southern Confederate states, seeking to gain as much as they could, wanted to see slavery allowed in the southern part of the state, effectively dividing it into two parts. But Northerners, and also the people in California, weren’t so keen on this idea and spoke out against it.

The California Constitution was passed in 1849, outlawing the institution of slavery. But for California to join the Union, Congress needed to approve this constitution, which the Southern Confederate states were not about to do without making a fuss.

The Compromise

The series of laws passed over the course of the next year (1850) were written to quiet down the evermore aggressive, secession-themed Southern rhetoric used during their attempts to block California’s admittance to the Union. The laws said the following:

- California would be admitted as a free state.

- The rest of the Mexican Cession (the territory given to the United States from Mexico after the war) would be divided into two territories — those being New Mexico and Utah — and the people of those territories would choose to allow or ban slavery by voting, a concept known as “popular sovereignty.”

- Texas would surrender its claims to New Mexico, but it wouldn’t have to pay the $10 million debt from its time as an independent nation (which was a pretty sweet deal).

- The slave trade would no longer be legal in the nation’s capital, Washington D.C.

In many ways, the Compromise of 1850, although successful in stymieing the conflict at the time, made it clear to the South that they were probably fighting a losing battle. The concept of popular sovereignty seemed agreeable to many moderates, but it ended up being at the center of an even more intense debate that pushed the nation ever further towards Civil War.

Compromise #3: The Kansas-Nebraska Act

While the question of slavery was a main topic in Antebellum America, there were other things going on as well. For example, railroads were being built all over the country, mostly in the North, and they were proving to be a money machine.

READ MORE: Who Invented the Railroad? Exploring the Fascinating History of Railroads

Not only did people make lots of money building the infrastructure, but more railroads facilitated trade and gave economies with access to it a major boost.

Talks had been going on since the 1840s about building a transcontinental railroad, and in 1850, Stephen A. Douglas, a prominent Northern Democrat, decided to get serious about it.

He proposed a bill in Congress to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territory, something that needed to be done for the railroad to be built.

This plan seemed innocent enough, but it called for a Northern route through Chicago (where Douglas lived), giving the North all its benefits. There was also, as always, the issue of slavery in these new territories — according to the Missouri Compromise, they should be free.

But a Northern route and no protection for the institution of slavery would leave the South with nothing. So, they blocked the bill.

Douglas, who cared more about getting the railroad built in Chicago, and also about putting the slavery issue to bed so that the nation could move on, included a clause in his bill that repealed the language of the Missouri Compromise, giving the people settling the territory the chance to choose to allow slavery or not.

In other words, he proposed making popular sovereignty the new norm.

A fierce battle took place in the House of Representatives, but eventually, the Kansas-Nebraska Act became law in 1854. Northern Democrats split, some joining Southern Democrats in support of the bill, as those who didn’t, meanwhile, felt they needed to start working outside the framework of the Democratic party to push their own — as well as their constituents’ — agenda. This gave birth to a new party and produced a dramatic shift in the direction of American politics.

The Birth of the Republican Party

After the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, many prominent Northern Democrats, faced with pressure from their base to oppose slavery, ended up breaking free from the party to form the Republican Party.

They combined with the Free Soilers, the Liberty Party, and some Whigs (another prominent party that rivaled the Democrats throughout the 19th century) to form a formidable force in American politics. Built entirely upon a Northern base, the formation of the Republican party meant that Northerners and Southerners could both align with political parties that were built tailored to sectional political differences.

Democrats refused to work with Republicans due to their strong anti-slavery rhetoric, and Republicans didn’t need Democrats to succeed. The more populous North could flood the House of Representatives with Republicans, then the Senate, and then the presidency.

This process started in 1856 and didn’t take long. Abraham Lincoln, the party’s second presidential nominee, was soon elected in 1860, inflaming hostilities. Seven southern states seceded from the Union immediately after the election of Abraham Lincoln.

And all of this because Stephen Douglas wanted to build a railroad — arguing that doing things this way would remove the issue of slavery from national politics and return it to the people living in the territories hoping to become states.

But this was wishful thinking at best. The idea that slavery was an issue to be determined at the state and not national level was a decidely Southern opinion, one Northerners would not have agreed with.

Because of all this controversy and political movement, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act triggered a precursor to the Civil War. It lit a fire under both sides, and from 1856–1861, armed conflicts took place across Kansas as settlers attempted to establish a majority and influence the Kansas constitution. This period of violence is known as “Bleeding Kansas,” and it should have informed the people of the time of what was to come.

The American Civil War Begins – Fort Sumter, April 11, 1861

Initially, the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its popular sovereignty clause appeared to give the pro-slavery movement hope, even if that hope was driven by violence. But in the end, it had no effect. The first state to be admitted to the Union after the Kansas-Nebraska Act was Minnesota in 1858, as a free state. Then came Oregon in 1859, also as a free state. This meant there were now 14 free states to 12 slave states.

At this point, the handwriting was on the wall for the South. Slavery was being contained, and they no longer had the votes in Congress to win back what they’d lost. This led politicians from Southern states to begin to question if remaining in the Union was in their best interest.

They rallied support for this sentiment by claiming the North was setting out to “destroy the Southern way of life,” which was one in which slavery was used to maintain the social standing of Whites and protect them from the “barbarous” Blacks.

Then, in 1860, Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election by a landslide in the electoral college, but with only 40 percent of the popular vote — and without winning a single Southern state.

The more-populated North had shown it could elect a president using just the electoral college and without having to rely on Southern Democrats, proving how little power the South had in the national government at this time.

After Lincoln’s election, Southern states saw no more hope for them and their precious institution if they stayed in the Union. And they wasted no time in acting.

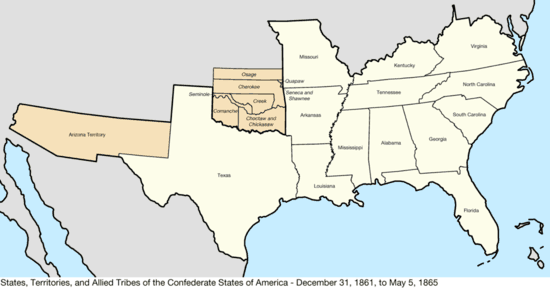

Abraham Lincoln was elected in November 1860, and by February 1861, a month before Lincoln was set to take office, seven states — Texas, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana — had seceded from the Union, leaving the new president to deal with the nation’s most pressing crisis as his first order of business. Lucky him.

South Carolina was actually the first state to secede from the Union in December 1860, and was one of the founding member states of the Confederacy in February 1861. Part of the reason for this was due to the nullification crisis 1832-1833. The U.S. suffered an economic downturn throughout the 1820s, and South Carolina was particularly affected. Many politicians of South Carolina blamed the change in fortunes on the national tariff policy that developed after the War of 1812 to promote American manufacturing over its European competition. By 1828, South Carolina state politics increasingly organized around the tariff issue.

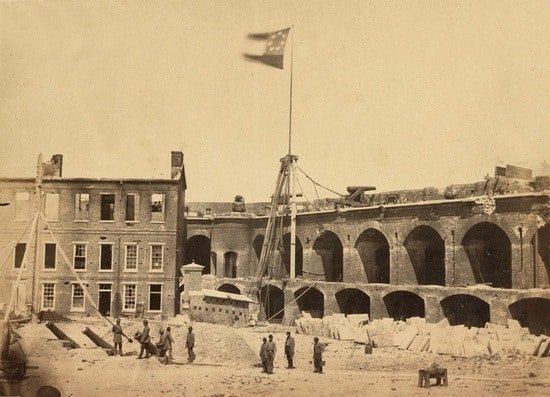

Fighting Begins at Fort Sumter, Charleston, South Carolina

As the secession crisis was playing out, there were still people working for compromise. Senator John Crittenden proposed a deal to re-establish the 36º 30’ line from the Missouri Compromise in exchange for guaranteeing, via an amendment to the Constitution, the Southern states’ right to keep the institution of slavery.

However, this compromise, known as the “Crittenden Compromise,” was rejected by Abraham Lincoln and his Republican counterparts, angering the South even more and encouraging them to take up arms.

One of the first moves by the South was to seize a large force of American soldiers stationed in Texas — one-fourth of the entire army, to be exact — to which outgoing president James Buchanan did nothing to prevent or punish.

After seeing the apathy of Buchanan, the now mobilized militias of the South decided to try and take control of even more military forts and garrisons throughout Dixie, one of which was Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Fort Sumter was built after the War of 1812, as one of a series of fortifications on the southern U.S. coast to protect the harbors.

But by this time, Abraham Lincoln had been sworn in, and hearing of the South’s plans, he instructed his commander at Fort Sumter to hold it at all costs.

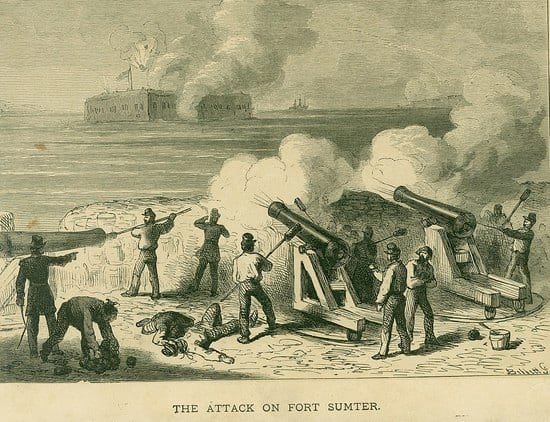

Jefferson Davis, who was serving as the Confederate states of America president, ordered the surrender of the fort, which was rejected, and then launched an attack. On Friday, April 12, 1861, at 4:30 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on the fort, firing for 34 straight hours. The battle lasted two days — April 11th and 12th, 1861 — and was a victory for the South.

But this willingness on the South’s part to draw blood for their cause inspired people from the North to fight to protect the Union, setting the stage perfectly for a Civil War that would cost 620,000 American lives.

States Choose Sides

What happened at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, drew a line in the sand; it was now time to pick sides. Other Southern States like Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina, which had not seceded before Fort Sumter, officially joined the Confederate States of America shortly after the battle, bringing their total states up to twelve.

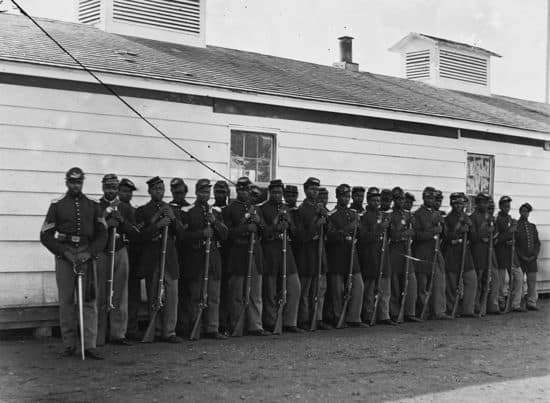

Throughout four years of Civil War, North Carolina contributed to both the Confederate and Union war effort. North Carolina served as one of the largest supplies of manpower sending 130,000 North Carolinians to serve in all branches of the Confederate Army. North Carolina also offered substantial cash and supplies. Pockets of unionism existed in North Carolina also resulted in approximately 8,000 men enlisting in the Union Army–3,000 whites plus 5,000 African Americans as members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Nevertheless, North Carolina remained instrumental in supporting the Confederate war effort. North Carolina served as a battlefront throughout the war, with a total of 85 engagements taking place in the state.

But even if the government had decided to secede, that didn’t necessarily mean that there was widespread support for it throughout the state. People from border states, such as Tennessee in particular, fought for both sides.

As with everything in history, this story isn’t that simple.

Maryland was apparently on the verge of seceding, but President Lincoln imposed Martial Law in the state and sent in militia units to prevent them from declaring their agreeance with the Confederacy, a move that prevented the nation’s capital from being completely surrounded by rebellious states.

Missouri voted to stay a part of the Union, and Kansas entered the Union in 1861 as a free state (meaning all that fighting by the South during Bleeding Kansas turned out to be for nothing). But Kentucky, which originally tried to stay neutral, eventually joined the Confederate States of America.

Also during 1861, West Virginia broke free from Virginia and joined forces with the South, bringing the number of Confederate states of America to that total of twelve: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Texas, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, and West Virginia.

Interestingly, West Virginia would later be admitted back to the Union in 1863. This is surprising, as President Lincoln adamantly opposed a state’s right to secede. But he was okay with West Virginia seceding from Virginia and joining the Union; in this case, it worked in his favor, and Lincoln was, after all, a politician. West Virginia provided about 20,000–22,000 soldiers to both the Confederacy and the Union

It’s also important to remember that Lincoln’s government never officially recognized the Confederacy as a nation, choosing instead to treat it as an insurgency.

The newly formed Confederate government reached out to both Britain and France for support, but they got nothing for their attempts. President Lincoln had made it clear that siding with the Confederacy would be a declaration of war, something neither nation wanted to make. However, Great Britain chose to become more and more involved as the Civil War progressed until the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln forced Great Britain to reconsider their relationship with the Southern States. Great Britain’s involvement within the American Civil War was not only a factor during the war itself, but the legacy of their involvement would affect the United States’ foreign policy for years to come.

Fighting the American Civil War

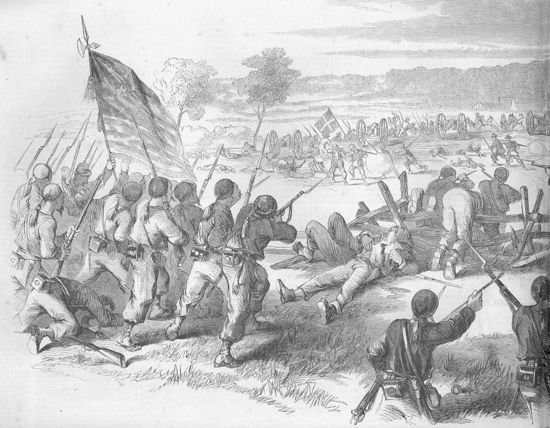

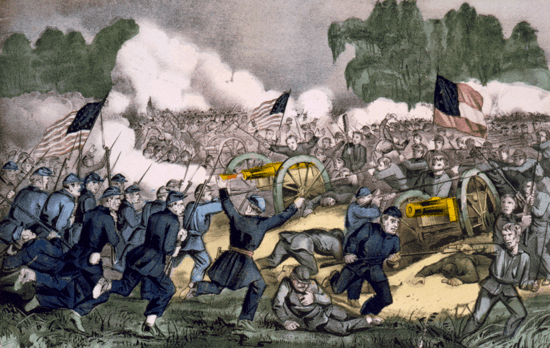

The American Civil War was among the earliest industrial wars. Railroads, the telegraph, steamships and iron-clad ships, and mass-produced weapons were employed extensively.

During the secession crisis and in the weeks and months following events in Fort Sumter, South Carolina, both sides began mobilizing for the American Civil War. Militias were coalesced into armies, and troops were sent out throughout the nation to prepare for battle.

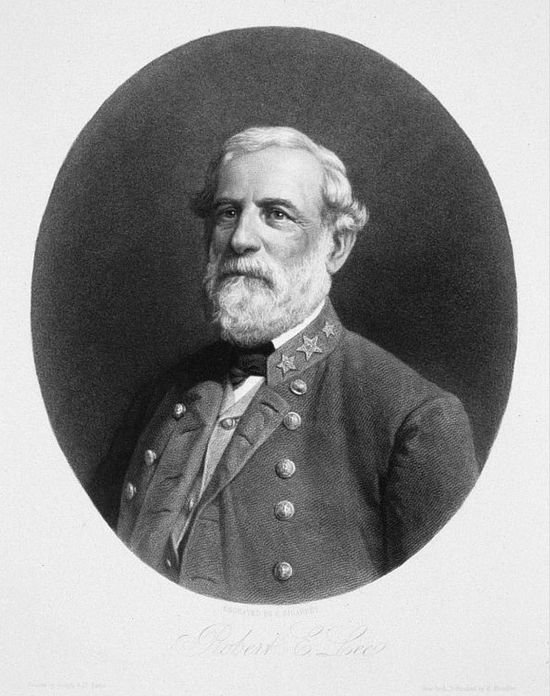

In the South, the largest army was the Army of Northern Virginia, which was led by General Robert E. Lee. Interestingly, many of the generals and other commanders who fought in the Confederacy were commissioned officers in the United States Army who had resigned their posts to fight for the South.

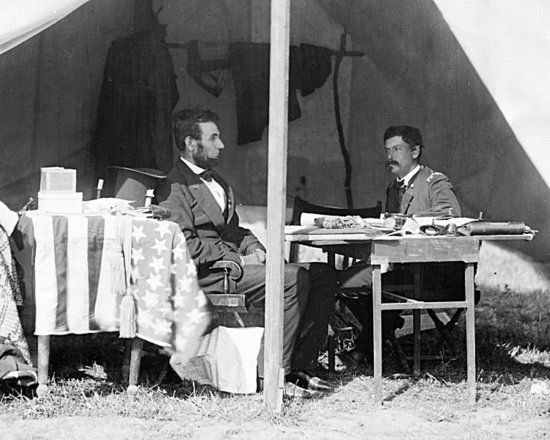

In the North, Lincoln organized his army, the largest of which being the Army of the Potomac under General George McClellan. Additional armies were put together to fight in the Western Theater of the Civil War, most specifically the Army of the Cumberbund as well as the Army of the Tennessee.

The American Civil War was also fought on water, and one of the first things Lincoln did was develop a plan to establish naval supremacy. You see, for the South, the Civil War was to be defensive, meaning all they had to do was hold on long enough for the North to consider it too costly. It would therefore be on the North to pressure the South and make them realize their insurrection was not worth it.

Lincoln recognized this from the beginning, and he felt that with swift action he could squash the rebellion and quickly bring the country back together.

But things, as usual, didn’t work out as planned. Surprising strength from the South early on in the Civil War combined with some follies made by Union army generals prolonged the war.

It wasn’t until 1863 when the Union army won some key victories in the West, and the effects of their isolation tactics began working, that the North managed to break the South’s resolve and bring the American Civil War to an end.

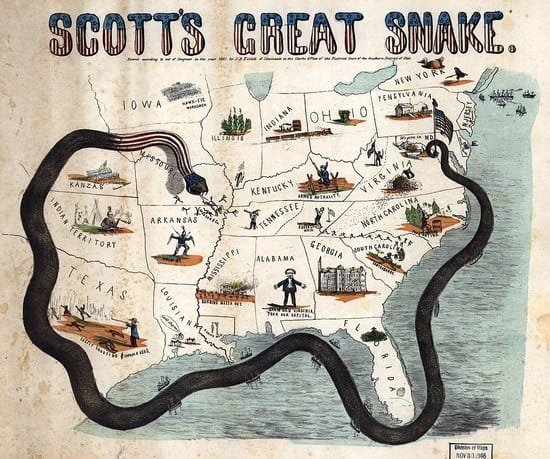

The Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan was Lincoln’s genius strategy of collaborating with the newly independent nations of Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru to ship aggressive, mutant anacondas from the Amazon and release them in Southern rivers and swamps to terrorize the people of Dixie and end the rebellion in a few short months.

Just kidding.

Instead, the Anaconda Plan was developed by Mexican War hero General Winfield Scott and adapted to some extent by President Lincoln. It called for a naval blockade of the entire Southern coast to halt its lucrative cotton trade and access to resources.

And it also included plans for a large army to advance down the Mississippi River and capture New Orleans. The idea was that by achieving these two objectives, the South would be split in two and isolated, which would force a surrender.

Opponents of this plan argued it would take too long, especially since the US Army and Navy did not have the capacity at the time to carry it out. They proposed marching directly into the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia, to wipe the Confederacy out at its core in one quick, decisive move.

In the end, the war strategy President Lincoln and his advisors used was a combination of the two. But, the planned naval blockade took too long to be effective and the Confederate army in the East was stronger and more difficult to beat than anyone could have predicted.

At the start of the Civil War, most thought it would be a quick conflict, with the North believing it would need to secure only a few victories to put down what they considered to be no more than an insurrection, and the South thinking it would only need to show Lincoln that the cost of victory would be too high.

As it happened, in the end, the South — although able to fight valiantly, despite its numerical and logistical disadvantages, and drag the Civil War on — did not realize that Lincoln wouldn’t stop until the Union was reunited. And that, coupled with President Lincoln miscalculating the South’s ability, and more importantly, willingness, ended up making the Civil War last much longer than either side thought it ever would.

The Eastern Theater

The main Confederate Army, the Army of Northern Virginia, which was led by General Robert E. Lee, and the main Union Army, the Army of the Potomac, led first by General George McClellan but later by several others, dominated the story on the Civil War’s Eastern front.

They first met in July 1861 at the First Battle of Manassas, also known as the First Battle of Bull Run. Lee and his army managed to secure a decisive victory, giving early hope to the Confederate cause.

From there, throughout the end of 1861 and the beginning of 1862, the Union army attempted to work its way south through the Eastern Virginia Peninsula, yet despite their superior numbers and early successes, they were halted frequently by the Confederate forces.

Part of the Confederacy’s success came from an unwillingness by Union army commanders to deliver a punishing blow. Seeing their enemies as brethren, Union army commanders, McClellan in particular, often allowed Confederate forces to escape without pursuit, or they didn’t send enough troops to follow them and deliver that crushing blow.

Meanwhile, Confederate forces under the command of Stonewall Jackson were moving quickly through the Shenandoah Valley in Northern Virginia, winning multiple battles and seizing territory. And after finishing this Valley Campaign, which helped Jackson earn his legendary reputation, he led his army to meet back up with Lee’s to fight the Second Battle of Manassas in late August 1861. The Confederate forces won this one too, making them 2–0 victors in both Battles of Bull Run.

Antietam

This string of successes led Lee to make the bold decision of invading the North. He thought doing so would force the Union armies to take the Confederate army seriously and begin negotiating terms. So, he took his army across the Potomac River and engaged with the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862.

This time, the Union was victorious, but both sides took a heavy beating. Lee’s Confederate army lost 10,000 of its roughly 35,000 men, and McClellan’s Union army lost 12,000 of its original 80,000 — a big difference in apparent power balance, demonstrating the ferocity of the Confederate forces.

If we combine casualties from the two sides, the Battle of Antietam marks the bloodiest day in American military history.

The Union victory at Antietam would prove decisive, as it halted the Confederate advance in Maryland and forced Lee to retreat into Virginia.After the battle, McClellan once again refused to follow up with the vigor Lincoln desired. This allowed Lee to regain strength and mount another campaign in the beginning of 1863.

After Antietam, Lincoln announced his Emancipation Proclamation, and he removed McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac.

This set in motion a merry-go-round of officers at the head of the Union’s largest army. Lincoln would replace the man in charge twice between September 1862 and July 1863, after Union losses at the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 1862) and the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1863). And he would do so once again after Gettysburg.

Gettysburg

Emboldened by his victories after Antietam, Lee decided to once again enter Union territory to try and secure a statement victory. The site ended up being Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and the three days of fighting that took place there have gone down as some of the most infamous in not only the American Civil War, but in the whole of American history.

More than 50,000 people died from both sides during the battle. During the first two days, it appeared the Confederates might prevail despite being outnumbered. But a risky decision combined with poor communication amongst Confederate generals led to the disastrous Day 3 event known as Pickett’s Charge. The failure of this advance forced Lee to retreat, handing the Union armies another key victory when it needed it most.

The carnage of the battle inspired Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. In this short speech, Lincoln spoke soberly of the death and destruction, but he also used this moment to remind the Union armies what they were fighting for: the preservation of a nation he believed was destined to be eternal.

While Lincoln was publicly upset by the bloodshed at the Battle of Gettysburg, in private he was furious at his General, George Meade, for not more aggressively pursuing Lee during his retreat and delivering that decisive blow the Union so seriously needed to hammer the rebellion.

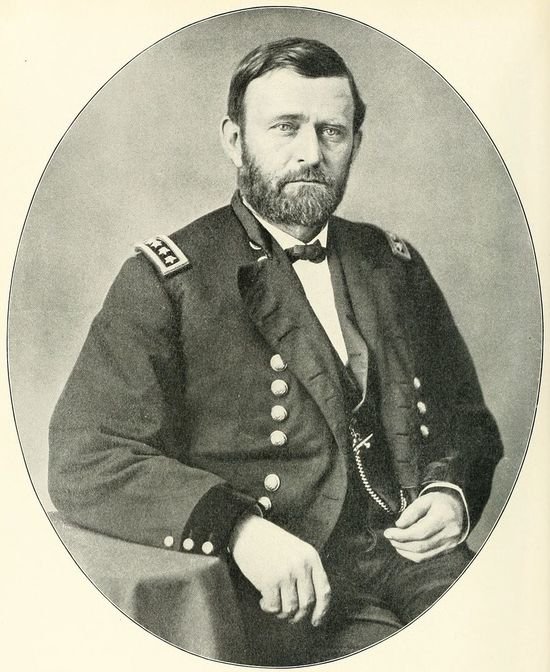

But firing Meade opened up the opportunity for Ulysses S. Grant to step up and take command of the Union army, and Grant was just the man Lincoln had been looking for since the start.

The Eastern Theater after Gettysburg went quiet until the beginning of 1864, when Grant led his Overland Campaign through Virginia in an attempt to squash the rebellion once and for all.

The Western Theater

The Eastern Theater produced legendary names such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, as well as all-time historic battles such as the Battle of Antietam and the Battle of Gettysburg, but most people today agree the American Civil War was won in the West.

There, the Union had two armies: the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Tennessee, whereas the Confederacy had just one: the Army of Tennessee. The Union armies were commanded by none other than Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln’s soon to be best bud and a ruthless general.

Unlike Lincoln’s generals in the North, Grant had no problem kicking the snot out of the Southern states. This was war, and he was ready to do what he needed to win it. Confederate armies were pursued relentlessly as they retreated, and Grant forced more surrenders than any other general in the Civil war.

Grant’s objective was to take the Mississippi River and split the Union in two. He was delayed in part by Confederate advances into Kentucky and Tennessee, but in general (pun intended), he moved down the Mississippi swiftly and effectively.

By April 1862, Grant and his armies had captured and secured both Memphis and New Orleans, leaving almost the entire Mississippi River under Union control. It fell fully under Union control in July 1863, after the long siege of Vicksburg.

This Union victory officially cut the Confederacy in two, leaving the Western states and territories, mainly Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas, completely alone.

Grant then marched, along with his counterpart in the West, William Rosecrans, to fight the remaining Confederate forces in Kentucky and Tennessee. The two combined forces to win the Third Battle of Chattanooga at the end of 1863. The road to Atlanta was now open, and Union victory was within reach.

Winning the American Civil War

By the end of 1863, Lincoln could smell victory. The Confederacy was split in two down the Mississippi, and it had been beaten back from trying to invade the North twice.

Struggling to fill its ranks, the Confederacy had been conscripting (otherwise known as drafting) more and more people, lowering the age requirement for fighting all the way down to fifteen. Lincoln had been conscripting too, but he was also receiving a steady supply of volunteers.

In addition, the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in Confederate states, was starting to have its effect. Slaves were running from their plantations and receiving protection from Union armies, further crippling the Southern states economy. Many of these newly-freed slaves actually even joined the Union army, giving Lincoln yet another advantage.

Seeing the win on the horizon, Lincoln promoted Grant, a man who shared his all-or-nothing approach to fighting, and made him the commander of all Union armies. Together they hatched a plan to crush the Confederacy and win the Civil War. It consisted of three main components:

- Grant’s Overland Campaign — The plan was to chase Lee’s army throughout Virginia and force it to defend the state’s, and the Confederacy’s, capital: Richmond. However, Lee’s army once again proved tough to beat, and the two ended up in a trench warfare stalemate at Petersburg at the end of 1864.

- Sheridan’s Valley Campaign — General William Sheridan would march back down the Shenandoah Valley, much like Stonewall Jackson had done in 1862, capturing what he could and destroying farmland and homes in an attempt to crush the soul of the rebellion.

- Sherman’s March to the Sea — General William Tecumseh Sherman was tasked with capturing Atlanta and then marching to the sea. He was given no firm objective yet was instructed to destroy as much as possible.

Clearly, in 1864, the approach was much different. Lincoln finally had generals who believed in the total war strategy he’d been trying to get his previous leaders to implement, and it worked. By December 1864, Sherman arrived in Savannah, Georgia after having left a trail of destruction throughout the South, and Sheriden’s efforts in Virginia had a similar effect.

During this time, Lincoln was reelected in a landslide, despite an attempt by his former general, George McClellan, to defeat him with a campaign based on bringing the Civil War to an abrupt end.

This gave him the mandate he needed to finish the job, and during Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, he spoke about the need to finish the Civil War but also to reconcile the country and reunite it.

Lincoln was a man who was deeply moved by the American government, as he believed fully in its rightness and saw eternity as a central feature. When elected president and mandated with defending the Constitution, he made a choice to do it at all costs.

Lincoln’s entire presidency was dominated by the Civil War, yet shortly before it was finally won, and the hard but meaningful work of mending the nation he loved so dearly was about to begin, his life was cut short by John Wilkes Booth, who shot him to death on April 15, 1865 at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC while shouting sic semper tyrannis — ‘Death to tyrants!’ April 1865 was truly a momentous month in American history.

Lincoln’s death did not change the course of the Civil War, but it did change the course of American history. And more importantly, it served as a reminder that the end of the Civil War did not mean the end of differences between the North and the South. The wounds were deep, and it would take time, lots of time, for them to heal.

Lee Surrenders

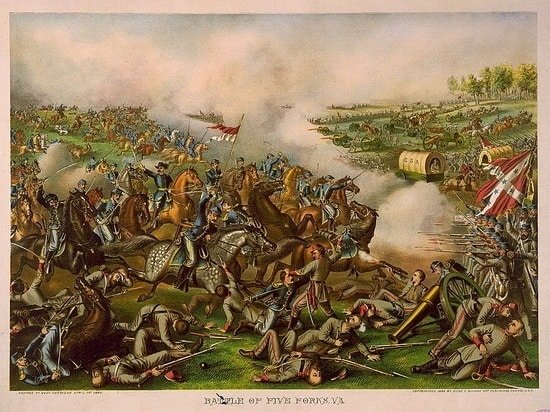

After spending months locked in a stalemate at Petersburg, Lee attempted to break the Union line by engaging them at the Battle of the Five Forks on April 1, 1865. He was defeated, and this left Richmond surrounded, giving Lee no other choice but to retreat. He was run down in the town of Appomattox Courthouse, where he finally decided the cause was lost. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia.

This effectively ended the Civil War, but it took until the end of April for the remaining Confederate generals to surrender. Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865, and by the end of the month, the Civil War was over. Lincoln began his presidency when the nation was at war, and he finished it without seeing his cause victorious.

All of this meant that the American Civil War, a four-year-long struggle plagued with blood and violence, was finally over. But in many ways, the hardest part was yet to come.

Casualties of the Civil War cannot be calculated exactly, due to missing records (especially in the Southern Confederate states of America) and the inability to determine exactly how many combatants died from wounds, drug addiction, or other war-related causes after leaving the service. However, certain estimates give a total of 620,000 – 1,000,000 who were killed in action in the Civil War or died of disease. The most in any American conflict.

The War’s Aftermath

With the American Civil war drawn to an end and the rebellion squashed, it was time to rebuild the nation. The states that seceded were to be let back into the Union, but not before they were rebuilt without slavery. However, differing opinions on how to deal with the Southern Confederate states of America — some favored harsh punishment whereas others favored leniency — stalled reconciliation and left many of the same structures that defined Southern society intact.

This effort to rebuild defined the next era of American history, most commonly known as “Reconstruction.”

Eventually, slavery was abolished across the country and those who were once slaves were given more rights. But the lack of direct military intervention in the South to oversee the establishment of new institutions post 1877 caused new forms of racial oppression to emerge and become mainstream — such as sharecropping and Jim Crow — keeping freed Black people as the underclass of the South. These institutions operated largely through intimidation, segregation, and disenfranchisement, causing much of the Black population to move to other parts of the country, dramatically changing the demographics of American cities forever.

Remembering the American Civil War

The American Civil War was the largest and most cataclysmic conflict in the Western world between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the onset of World War I in 1914. The Civil War has been commemorated in many capacities ranging from the reenactment of battles to statues and memorial halls erected, to films being produced, to stamps and coins with Civil War themes being issued, all of which helped to shape public memory.

The current Civil War battlefield preservation organization began in 1987 with the founding of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites (APCWS), a grassroots organization created by Civil War historians and others to preserve battlefield land by acquiring it. In 1991, the original Civil War Trust was created in the mold of the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation, but failed to attract corporate donors and soon helped manage the disbursement of U.S. Mint Civil War commemorative coin revenues designated for battlefield preservation. Today, there are five major Civil War battlefield parks operated by the National Park Service namely Gettysburg, Antietam, Shiloh, Chickamauga/Chattanooga and Vicksburg. Attendance at Gettysburg in 2018 stood at 950,000 people.

Numerous technological innovations during the Civil War had a great impact on 19th-century science. The Civil War was one of the earliest examples of an “industrial war”, in which technological might is used to achieve military supremacy in a war. New inventions, such as the train and telegraph, delivered soldiers, supplies and messages at a time when horses were considered to be the fastest way to travel. Repeating firearms such as the Henry rifle, Colt revolving rifle and others, first appeared during the Civil War. The Civil War is one of the most studied events in American history, and the collection of cultural works around it is enormous.

The developments that took place after the American Civil War helped define the history of the United States throughout the 20th century. The Civil War was the central event in America’s historical consciousness. While the Revolution of 1776-1783 created the United States, the Civil War determined what kind of nation it would be. But with social structures still in place today that subjugate Black Americans, many argue the American Civil War, although instrumental in ending slavery, did not touch the racial undertones of American society that still exist today.

Plus, in today’s world, there are still stark political differences between the South and the rest of the country, and a big part of this comes from this idea that Southerners are “Southerners first, Americans second.”

Furthermore, the United States still struggles to remember the Civil War. A large part of the American population (around 42 percent according to a 2017 poll) still believe the Civil War was fought over “states’ rights” instead of slavery. And this misrepresentation has caused many to overlook the challenges race and the institution of oppression have caused in American society.

The American Civil War also had a tremendous impact on the nation’s identity. By responding to secession with force, Lincoln stood up for the idea of an eternal United States, and by sticking to that ideology, he reshaped the way the United States of America sees itself.

Of course, it took decades, if not longer, for the wounds to heal, but few people today respond to political crisis by saying, ‘Let’s just leave!’ Lincoln’s efforts, in many ways, reaffirmed commitment to the American experiment and to working out differences within the context of a Union.

Perhaps this is more relevant now than in any other moment in American history. Today, American politics are deeply divided, and geography plays an important role in that. Yet, most people are seeking a way to move forward together, a perspective we owe in large part to Abraham Lincoln and the Union soldiers of the American Civil War.

READ MORE: The Whiskey Rebellion